Epistemic Injustice

Epistemic Injustice by Miranda Fricker was the 6th book assigned in the philosophy book club I have participated in for several years. We have explored it over the past 8 months. It is a profoundly challenging and intellectually dense book. During our reading, it offered me invaluable insights.

In this short essay, I aim to distill my key takeaways. I will also include some visual interpretations inspired by my own understanding and enriched during the course of our discussions.

Justice is the Recognition of the Existence of Injustice

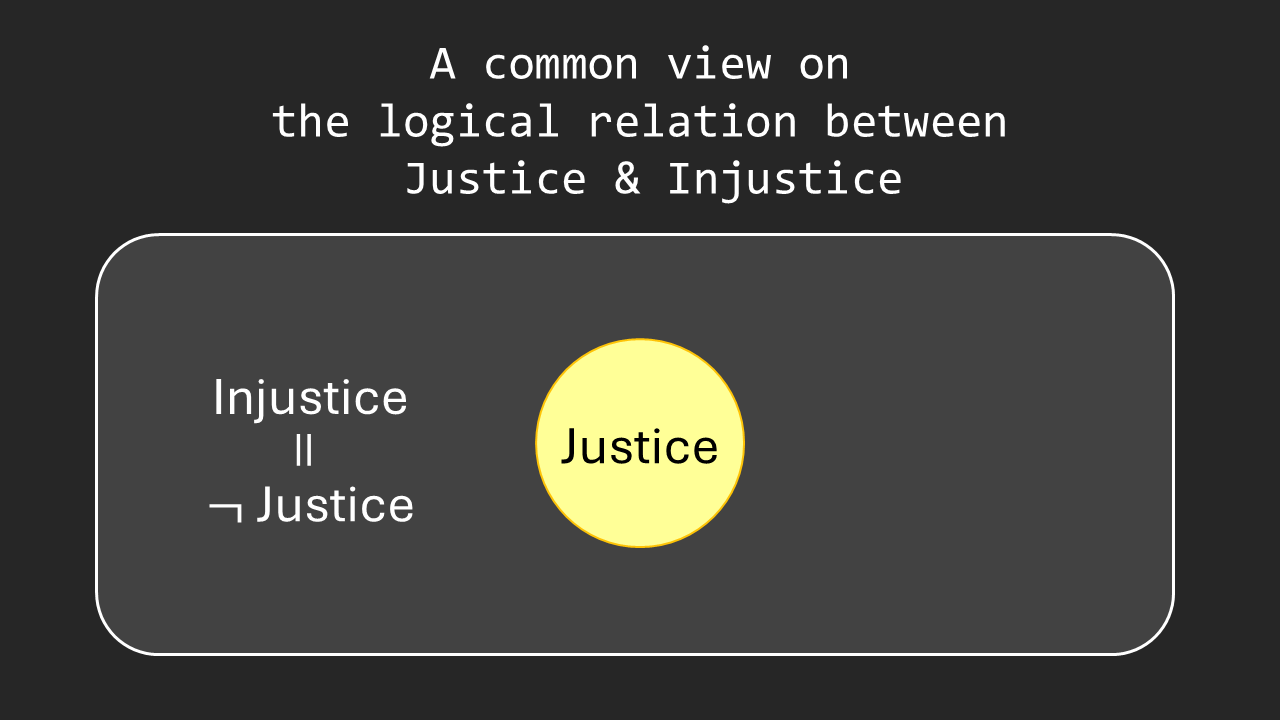

Justice. When we hear this word, it often provokes mixed reactions—perhaps even skepticism or outright rejection. Justice typically connotes moral and legal rightness, embodying ideals such as fairness and equality. It is often regarded as the foundation of a community or society. Yet justice can also serve as a justification, a means to legitimize decisions, policies, or actions. However, what one considers justice may starkly contrast with another's justice. In the real world, there is no absolute or universal justice. Justice, in this sense, becomes an illusion. But what about injustice?

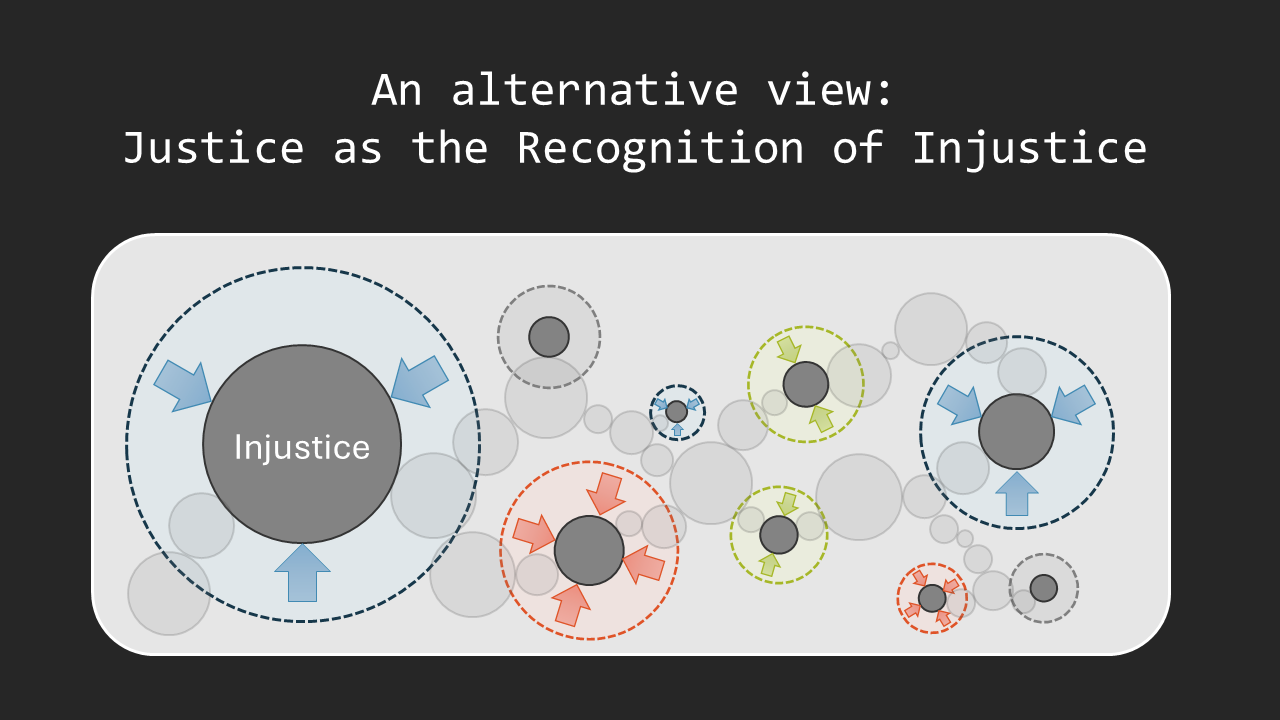

Linguistically, injustice, as the negation of justice, signifies “not justice” or “absence of justice”. Injustice, therefore, inherently references a prior understanding of justice. At first glance, this might suggest that injustice, like justice, suffers from definitional impossibility. But what if we all acknowledged that justice is a mere illusion and accept that each one of us, through our perceptions and actions, inevitably contributes in some way to injustice? Could this shift in recognition allow us to redefine injustice not as an abstract concept but as something tangible in the exercise of individual abilities in practices?

Unlike justice, which depends on abstract ideals, injustice may serve as a more accessible ground where collective understanding can be achieved. The pursuit of justice requires agreement on its abstract principles— a consensus that seldom, if ever, exists due to its subjectivity. In contrast, while injustice undeniably manifests in societal issues, confronting injustice does not rely on shared ideals but instead calls for recognition of its intrinsic connection to each individual’s attitudes and actions.

By reframing injustice as a matter of individual accountability, the focus shifts from theoretical debates about societal ideals to introspection and self-reflection. This perspective emphasizes the individual agency and directs attention towards viable changes in one’s own attitudes and practices, making the issue tangible and transformative at the individual level.

The book opens with a thought-provoking quotation from Judith Shklar, which illuminates the pervasive presence of injustice— a space this book seeks to explore:

Every volume of moral philosophy contains at least one chapter about justice, and many books are devoted entirely to it. But where is injustice? To be sure, sermons,… drama, and fiction deal with little else, but art and philosophy seem to shun injustice. They take it for granted that injustice is simply the absence of justice, and that once we know what is just, we will know all we need to know. That belief may not, however, be true. One misses a great deal by looking only at injustice. The sense of injustice, the difficulties of identifying the victims of injustice, and the many ways in which we all learn to live with each other’s injustices tend to be ignored, as is the relation of private injustice to the public order.

—Judith Shklar, The Faces of Injustice, 15

Epistemic Injustice

Every individual wears metaphorical glasses through which they perceive the world. These glasses magnify topics of personal relevance, such as a professional’s focus on their specific field of expertise or an environmentalist’s focus on ecological conservation, while often blurring those outside their knowledge or focus. They may tint perceptions with biases, coloring opinions in ways that reinforce these perspectives, such as favoring progressive or conservative values, or aligning with specific religious or cultural ideologies. In extreme cases, these glasses create blind spots, rendering certain aspects of reality entirely unseen or misunderstood.

Individuals are not born wearing these glasses. Instead, they develop over time, molded and refined by life experiences, acquired knowledge, and interactions. These are profoundly influenced by the societal environment in which one is raised, reflecting its norms, values, and cultural context. The way people perceive the world is, hence, not innate; it is significantly shaped by subjective perceptions, prejudices, and prior judgments, all of which have been formed through life experiences.

Testimonial Injustice

In the context of communication, these metaphorical glasses have a profound influence on the exchange of information between a speaker and a hearer. They shape not only how the message is delivered but also whether it is received as credible. The hearer must evaluate what the speaker says, whether they may constitute valuable insight or are erroneous. In other words, the hearer must evaluate the speaker's credibility while listening. Evaluation always necessitates some measure of the speaker's credibility. A useful analogy for this evaluation process is the “scouter” from Dragon Ball, which assesses an individual’s power level. Similarly, one could imagine assigning a credibility score to a speaker, perhaps ranging from -100 to 100. But what is this scale founded upon?

The hearer relies on a metric to determine the speaker’s credibility. All evaluations are relative to that scale. However, there is no universal or completely objective scale for such evaluations. The glasses unconsciously alter what the hearer perceives as “neutral” or unbiased. Testimonial injustice can occur in such contexts, where a speaker’s word is discredited or devalued due to prejudice associated with their identity—such as race, gender, or socioeconomic background. As a result, credible information may be unjustly dismissed before being properly considered.

Addressing testimonial injustice requires first recognizing the existence of systematic biases that create credibility deficits for certain groups. Once these biases are acknowledged, it compels individuals to actively recalibrate the “neutral” point on their internal evaluation scales to neutralize the effects of prejudice. This recalibrations demands intentional effort and critical self-reflection—examining assumptions and actively seeking alternative perspectives. By continually polishing the glasses, individuals can cultivate greater fairness and objectivity, ultimately fostering, a more open-minded and inclusive discourse can be achieved.

Virtue

Fricker introduces the concept of virtue to define the qualities a truly good listener should embody. To illustrate this, she provides two intuitive examples.

The first example is a woman referred to as the ruthless truth-seeker. She is highly motivated by the pursuit of truth but shows no regard for justice. As a boss of a large advertising company, she has no interest in the well-being of her employees. However, she is committed to making unprejudiced judgements about their credibility because she recognizes that it is essential for efficiently harvesting their knowledge and creative ideas.

The second example is a fair-minded conversationalist. He has no interest whatever in the truth or falsity of what he hears during dinner party conversations. However, by a sense of justice, this anxious guy is very concerned to avoid any injustice towards his guests. This concerns compels him to neutralize any prejudice in his credibility judgements.

At first glance, both might appear to act justly. Yet, people would hesitate to attribute the virtue to them. To clarify this point, she references Aristotle’s criteria for virtuous acts:

Virtuous acts are not done in a just or temperate way merely because they have a certain quality, but only if the agent also acts in a certain state, viz.

-1. if he knows what he is doing,

-2. if he choose it, and choose it for its own sake, and

-3. if he does it from a fixed and permanent disposition

The ruthless truth-seeker neutralizes prejudice solely for her own benefit. If her self-interest were no longer at stake, she would quickly abandon the self-discipline required to resist prejudice. Similarly, the fair-minded conversationalist, whose primary concern is to avoid insulting his guests, would behave entirely differently once the dinner is over and the context no longer demands his careful judgement.

These examples demonstrate that actions in practice alone are not sufficient; it calls for cultivating a virtuous disposition to become a truly virtuous listener.

Hermeneutical Injustice

Consider a relationship between a supervisor and a female worker in a workplace before the concept of “sexual harassment” was widely recognized. Because the term “sexual harassment” did not exist, the supervisor was unaware that his actions were inappropriate. Meanwhile, the woman experienced discomfort but lacked language to articulate her experience. Until the concept of sexual harassment was established and acknowledged, such behavior remained unrecognized and unaddressed.

This situation exemplifies what the book refers to as a lack of hermeneutical resources. It can be compared to a world only partially illuminated: we can only perceive the lit areas, while the unlit regions remain obscured, leaving us unable to recognize what lies within them. The placement of these metaphorical lights is often unjustly determined by societal structures and mass media, which inherently introduce biases in determining what is brought into the light and what remains in darkness.

Recognizing the existence of these unlit areas—experiences and concepts that lack recognition—is essential. By expanding the illuminated zones, we can create a more inclusive society that acknowledges and address marginalized experiences.

Distance in Recognition

An important aspect that emerged during the discussion of hermeneutical injustice, its associated resources, and the act of understanding through their use—though not explicitly mentioned in the book—was the significant influence of both physical and epistemic distance.

The transmission of information requires time related to the physical distance it must traverse, and the loss or degradation of information similarly increases with distance. For instance, as I currently reside in France, I cannot perceive events occurring in Japan with the same depth as someone physically present there. Information accessed through online news sources does not convey the tangible nuances and genuine emotional context that one might experience locally.

This sense of distance is not limited to geographical separation. It also extends to social constructs, such as race, class, or culture. My understanding of the thoughts and experiences of individuals outside my immediate social circle often relies on depictions encountered through media. Beyond these mediated portrayals, I lack direct familiarity or insight into their realities.

This reflection underscores how both physical and conceptual distances influence our ability to engage with hermeneutical resources. These distances limit our capacity to fully grasp the perspectives and experiences of others. By recognizing and respecting these distances, we can approach understanding with greater caution. This awareness allows us to interpret others’ experiences more responsibly, accounting for the distinct contexts that shape their realities.

Did you like this article ? A coffee helps keep this project thriving — thank you!